1 Introduction

Learning Outcomes

- Students can explain how sustainability science approaches (mode-2 science) differ from traditional science approaches (mode-1 science)

- Students can explain the role of ethics in sustainability science

1.1 Sustainable development - Sustainability

It is becoming increasingly evident that disciplinary approaches and disciplinary specializations are often insufficient to understand and address the complex challenges and wicked problems of the 21st century. Sustainable development issues, in particular, extend across various scientific and thematic fields. This necessitates collaboration between disparate disciplines and other stakeholders. Thus, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity are considered to be essential research approaches in the field of sustainability science.

| Mode-1 science | Mode-2 science |

|---|---|

| Academic | Academic and social |

| Mono-disciplinary | Trans- and interdisciplinary |

| Technocratic | Participative |

| Certain | Uncertain |

| Predictive | Exploratory |

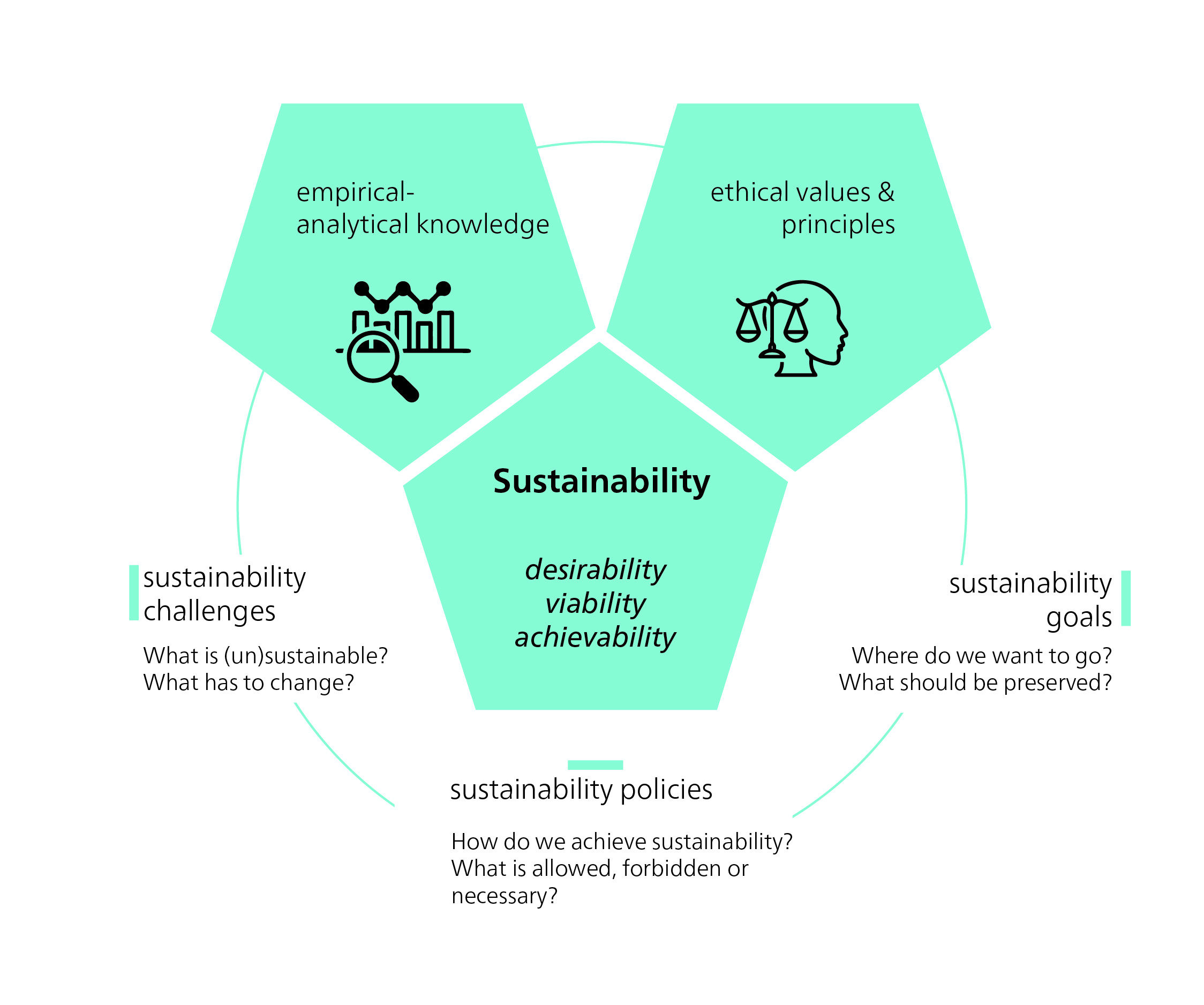

Sustainability science can be understood as an arena where “contributions from the whole spectrum of the natural sciences, economics, and social sciences” (Martens 2006, 38) meet. Sustainability science distinguishes itself from “traditional” sciences, so-called mode-1 sciences (see Table 1.1), since it follows the normative ideas of sustainability.

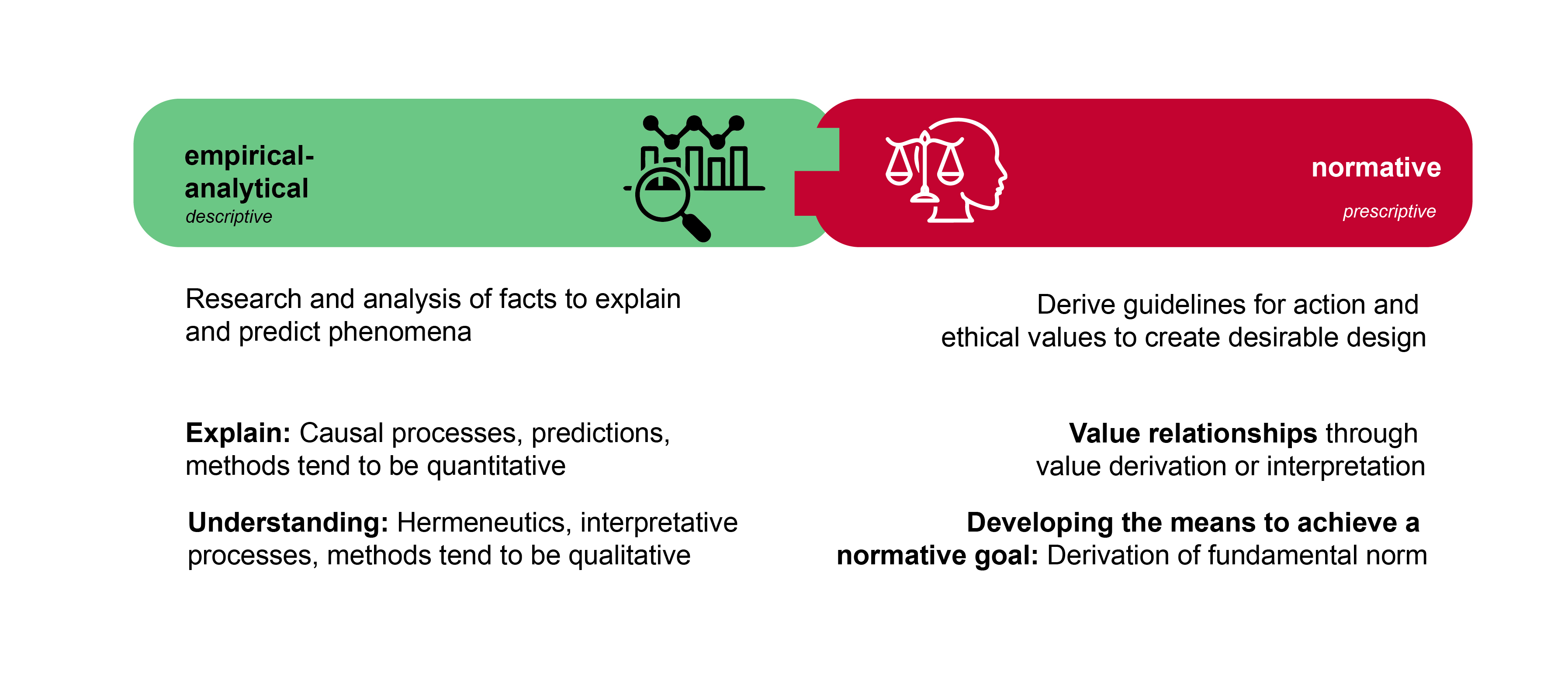

1.2 Normativity

As sustainable development is a normative model, it is important to distinguish between descriptive (empirical-analytical) research and prescriptive (normative) research. Descriptive statements describe the current state (“is”, e.g., vegetables contain a relatively high proportion of vitamins), while normative statements describe the ideal state (“ought”, e.g., you should eat vegetables). In everyday life, the distinction between “is” and “ought” is often not recognized, but it is crucial for science. Moreover, it is essential to recognize that individuals hold diverse perspectives, which can lead to diverging opinions regarding what is optimal or what sustainability should entail. Consequently, the concepts of “sustainability” or “sustainable development” cannot be regarded as impartial or neutral.

1.3 Ethics

Because sustainability/sustainable development is per se normative, this can lead to dilemmas (which means problems do not have an optimal solution). When looking at wicked problems such as biodiversity loss in agricultural areas there are multiple possible approaches: (1) protecting and promoting rare and extinction-threatened species and therefore reducing food production or (2) focusing on species with great abundance, which might be more important to economics and food security but would neglect rare species.

Depending on context, background and/or beliefs, some would prefer one approach over the other.

Ethics offers orientation and decision-making structures in order to find a suitable course of action in situations such as complex dilemmas. Ethics deals with the reflection and evaluation of moral actions and behaviour and is therefore the philosophical study of morals (moral norms, value judgments and institutions). There are numerous ethical approaches, two central ones of normative ethics being “teleological” and “deontological” approaches. Teleological ethics evaluates actions based on their goals or purposes, which are considered “good”. An example of this is utilitarianism (established by Jeremy Bentham), which judges actions according to how much utility or happiness they produce. Deontological ethics, on the other hand, focuses on duties and evaluates actions based on their characteristics rather than their consequences. An example of this is Kant’s duty-based ethics (Kantianism), which judges actions according to whether they comply with a moral rule or duty.

The concept of sustainability usually has a positive connotation, but it can be viewed from different perspectives. In order to function as a guiding principle (in an ecological, social, and economic sense), it requires clear criteria. But what grounds can we use to define these criteria?

According to Hirsch Hadorn and Brun (2007), “sustainable development” should:

- fulfil needs…

- … in a just way

- … with a view to people living today and in the future, and

- taking into account the diversity of values and the limit to which nature can be used.

The guiding principle of sustainable development is therefore not only the result of scientific research, but is first and foremost a normative, ethically based concept. It brings together “ethical and analytical ideas” and formulates “norms that express what is desirable and what should happen” (Renn et al. 2007, 39). As a result, sustainable development is a social process of negotiation and decision-making – of searching, learning, and gaining experience – that is guided by ethical considerations. Accordingly, sustainability research must always be aware of its involvement in social processes of perception and evaluation.